A few weeks ago on the podcast, I spoke with Molly St. Louis. Among many things, journalist, actor, marketer, Molly is someone who thinks deeply about performance. Not just in the theatrical sense, but in the way ideas perform out in the world.

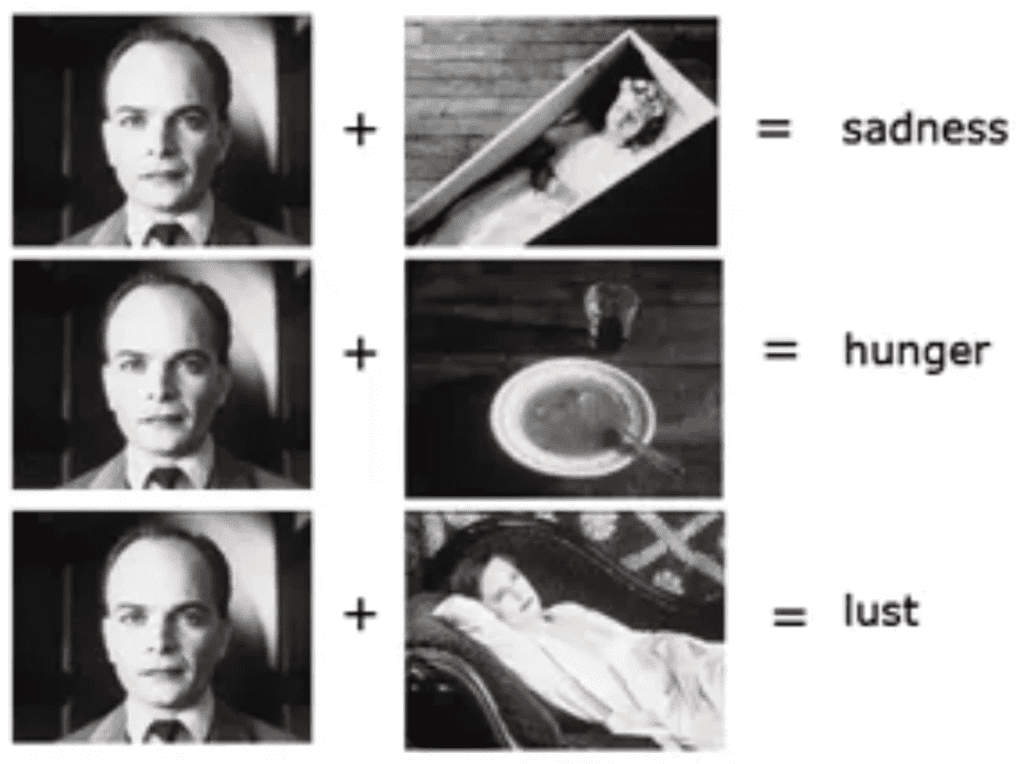

She brought up the Kuleshov Effect, a foundational concept in film editing.

The story goes like this:

A Russian filmmaker named Lev Kuleshov ran an experiment in the silent film era. He filmed a stoic actor, expressionless, looking directly into the camera. Then he spliced that footage with various other images: a bowl of soup. A child in a coffin. A woman reclining on a chaise lounge.

Audiences saw the man and said: “He’s hungry.” Or: “He’s grieving.” Or: “He’s in love.”

Same clip. Same face. No change in expression.

The meaning was created entirely by the frame surrounding it.

Molly learned this while studying video editing, but she uses it every day in B2B content strategy. When she builds narrative videos or virtual events, she thinks not just about the content itself, but what surrounds it—the audio design, the sequence of segments, the visual texture.

Most of what we talk about in marketing centers around the idea or the message itself; what this essay focuses on is everything surrounding the idea or message that impacts its delivery and perception.

Here, we’re diving into framing, signaling, and context.

Mise-en-scène

There’s another insight from my conversation with Molly St. Louis that’s been echoing in my mind ever since, and it’s worth pausing on: mise-en-scène.

It’s a film concept that literally means “placing on stage,” the composition of a scene, Also note that we’ve written and referenced the related “content operations mise-en-place” several times in the past.

It’s the way a director dresses the set, arranges the objects, selects the lighting, and frames the actor.

You’ve seen this even if you don’t know the term. Think of that scene in The Pursuit of Happyness: Will Smith sleeping on a bathroom floor, cradling his son, paper towels under his head, wearing a crumpled business suit. As Molly put it in our podcast:

“You know, instantly, without dialogue, that this is a father who’s loving, determined, and down on his luck, but still holding it together.”

The scene is speaking for him without saying a word.

Molly pointed out that we do the same thing in politics: flags behind candidates, children lined up in the background, construction workers in hard hats nodding solemnly. These aren’t random choices. They’re signals, many of which are consciously designed to send a certain message or emotion.

And you can, and should, bring that same level of intentionality to your work. As Molly put it:

“If you want your business to seem quirky and fun, you don’t say that out loud. You let the Legos on the office shelves do the talking.”

What surrounds your content, your brand, your people, speaks loudly. It’s the scene that gives the story its unconsciously legibility and conscious credibility.

The Authority in the Room (or Zoom)

When I was at HubSpot, I discovered that the source and the presentation of the idea mattered as much as the idea itself (or perhaps even more).

I had come from early stage startups before that, where speed was the modus operandi and there were fewer vectors to align. That’s to say, we didn’t waste a lot of time debating ideas, we just shipped and shipped fast.

It’s jarring to join a much larger company and realize that people do not operate the same way there.

We often use the word “politics” as an epithet to describe what is essentially the messy reality of working with other humans, and in fact, we’re always going to be doing “politics” regardless of the company size.

It just increases in importance as you scale, much of which is due to the natural complexity of more permutations of people and resources. There’s also a greater risk aversion, which, again, is natural. At a startup, your only real advantage is speed and agility. At a larger corporation, there’s more to lose if you get it wrong.

So I learned politics.

And one big learning I had is that if my ideas came vetted from outside the organization, they held more weight.

Luckily, I had hundreds of articles on the CXL blog (and across the web) on experimentation and analytics, which helped my credibility. I saw them shared naturally in different Slack channels at HubSpot.

I also spoke at conferences and meetups regularly and kept my own blog, which several executives at HubSpot read.

And of course, I put together the foundational slide decks and I set up the necessary meetings. But when I really wanted to push a bold idea through, I came at it from multiple angles, many of which were bolstered by outside credibility.

This is a large value add of outside consultants, who are often trusted merely because they are coming from Accenture or McKinsey. It’s not just the 2X2 matrix and pretty slide deck that people are paying for.

Digital PR and Prestige Content

I think about this when it comes to content as well, particularly the kind that includes original research or data points.

Certainly, one of the values is that you can publish it and it will drive some backlinks. You can gate the asset and it will drive some MQLs.

But another benefit is you can leverage it to be mentioned or syndicated in legacy or prestige media, which is taken much more seriously than a company blog.

There’s a reason we trust what we read in the New York Times more than what we see in a Twitter thread, even if they say the same thing. There’s a reason a quote hits harder in a TED Talk than in a bullet point slide.

Both the halo effect–our tendency to let one positive attribute influence how we perceive everything else, and the authority bias–our tendency to trust information more if it comes from perceived authority figures–play into this. If someone is polished, articulate, and cited by prestigious sources, we assume their ideas must be smart, too.

And that’s not a bug. It’s how our brains evolved to process overwhelming amounts of information.

Dress for Success

I didn’t always take this seriously.

Coming up in the Austin tech scene, a sport coat was a red flag – honestly quite strange if you saw someone wearing one around the city. That’s an Austin thing, but also a tech thing, with the historically prototypical outfit being a hoodie or startup tee. Nothing flashy; counter-signaling against ostentatious finance types, perhaps.

But context changes. Now I spend my days in conversation with CMOs, VPs, etc., and I live in New York City, where it’s…well, it’s a very fashionable city. Even on Zoom, when I’m talking to current or potential clients, my free startup tee wasn’t really signaling competence or respect. It was closer to “I just rolled out of bed and maybe hit a vape before this call.”

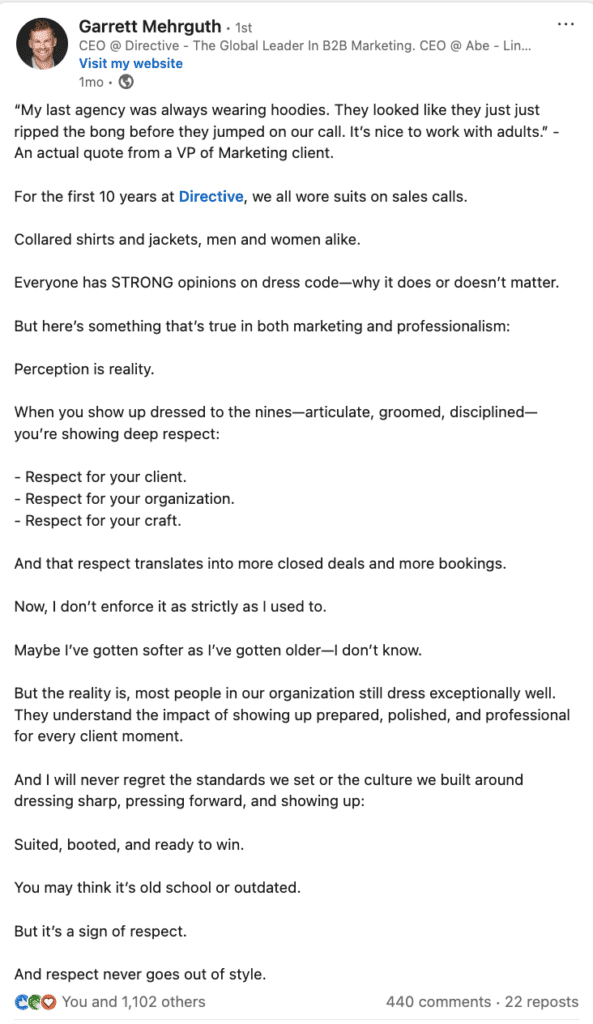

Garrett Mehrguth from Directive nailed this with a story he shared on LinkedIn:

Now, this is a fluid and dynamic arena. You can’t just dictate a simple rule like “wear a suit,” like you could in the past. It depends on the image you’re hoping to display, differentiation from the status quo, which industry you’re in, which customers you’re targeting, etc.

But the point is you’re always signaling something, regardless of whether you’re consciously trying to do so. Again, you may as well be intentional about these signals.

Print Magazines and the Cost of Credibility

This is one reason why we made a print magazine for our podcast (the other being that it was fun and we just wanted to).

Now, you can listen to the same episodes on Spotify. You can read the transcripts. We even publish the key takeaways online. The information is the same.

But when we hand someone the magazine, the reaction is completely different. People keep it. Display it. Read it cover to cover. Text us about it.

It feels real. It feels expensive. It feels like it took effort.

And effort, in today’s content landscape, which is often flooded with AI slop and low effort algorithm-bait, is a credibility signal.

This is costly signaling theory, a concept from evolutionary biology. The idea is that signals are only trusted when they’re hard to fake. A peacock’s tail isn’t useful for survival, it’s useful because it’s expensive (and possibly counterproductive to survival). It says, “I’m so fit I can carry this deadweight and still thrive.”

A tweet is cheap. A podcast clip is replicable. A print magazine means you cared enough to make something that can’t just be spun up in ChatGPT.

Same message. Different medium. Different impact.

The Subway Symphony

Of course, the most poetic example of all this is the Joshua Bell experiment.

Bell, one of the greatest violinists alive, once played in a D.C. subway station as part of a social experiment. He wore a baseball cap. Played a $3.5 million Stradivarius. Performed Bach and Schubert to rush-hour commuters.

Almost no one stopped.

He played the exact same set at the Boston Philharmonic, earning ~$60,000. In the subway, he made ~$32.

Same music. Same artist. Different context.

You’re Always Sending a Signal

Let me again admit that I’m a growth marketer who has rightfully come around to the power of brand, the irrational, and the emotional. The connotative.

It really came to me after reading Rory Sutherland’s Alchemy, and my appreciation for this stuff has only increased in recent years, as the marginal cost of creation is decreasing (increasing supply and, in many ways, leveling the playing field for median quality).

So I’ve turned my attention to what is scarce, what is value additive to the world, and what is hard to fake. And there are many of those things, but the context and the perception of what we’re creating is certainly one of them.

And the thing is, you can’t really opt out of signaling.

Consciously or not, the messages you’re putting out into the world are filtered through the perception of the receiver (which among many things, are influenced by the form, the medium, and the surrounding quality and credibility cues).

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to our Field Notes.