It’s folk wisdom that a startup’s only real advantage is speed.

In a war of resources, incumbents will crush you every time. What startups have is tempo — the ability to decide quickly, to learn quickly, to act before the window closes.

“Mere rate of shipping new features is a surprisingly accurate predictor of startup success.In this domain, at least, slowness is way more likely to be due to inability than prudence. The startups that do things slowly don’t do them any better. Just slower.”

It’s one of those truths that feels so obvious you almost overlook it. I’ve seen it in my own experience — from scrappy startups where momentum was oxygen, to Fortune 100 clients where one piece of content took a quarter to publish. The difference wasn’t intelligence or talent. It was friction.

But speed, in practice, is misunderstood. The corporate world has learned to fetishize “moving fast” without understanding what real velocity entails. The result is chaos disguised as urgency — a blur of meetings, approvals, and half-executed initiatives that create motion but not movement. A delirious whirlwind marked by thrashing and resulting in demoralization and stagnation.

Speed, done wrong, corrodes systems. Done right, it compounds learning. This is an essay about the latter.

The Physics of Motion

Speed has its own physics. It’s not a behavior but a set of forces: friction, drag, acceleration, feedback.

Acceleration is the rate of change; velocity is direction plus speed. The distinction matters. You can run very fast in a circle and end up nowhere.

Most organizations conflate motion with progress. They measure activity instead of acceleration. These are revolutions per minute. They are not distance traveled.

In physics, velocity is a vector. It requires direction. And the discipline of setting that direction (of focus and prioritization) is the first principle of clean speed.

Sam Altman put it well:

“Focus is a force multiplier on work.

Almost everyone I’ve ever met would be well-served by spending more time thinking about what to focus on. It is much more important to work on the right thing than it is to work many hours. Most people waste most of their time on stuff that doesn’t matter.Once you have figured out what to do, be unstoppable about getting your small handful of priorities accomplished quickly. I have yet to meet a slow-moving person who is very successful.”

Speed without focus is a centrifuge: it spins, it whirs, it generates heat – and accomplishes nothing.

Focus and Its Tradeoffs

Imagine deciding you want to “get fit.” That statement means nothing until you define it.

Do you want to run an ultramarathon, bench three plates, or step on stage at 6% body fat? You can’t do them all at once. Focus forces trade-offs.

So it goes with companies. The illusion of omnipotence kills velocity. You can pursue anything you want, but not simultaneously. The companies that move quickly are those that decide what not to do—the most unglamorous skill in business.

Frank Slootman wrote in Amp It Up that intensity itself is a forcing function:

“When you narrow focus, you are increasing the resourcing on the remaining priority. It doesn’t have to time-slice and compete any more with a bunch of other stuff. And then things begin to move, stuff is getting done, and we move to the next thing. Many people and organizations are focused a mile wide and an inch deep. It can’t be a surprise when they progress at snail’s pace. Log jams get broken when you sift through the reams of activities and you create fewer and clearer objectives. Do less, at a time. I’ve often felt that providence moves, too, when you un-clutter priorities. Like an Invisible Hand, all of a sudden things are on the move.”

When you compress effort into a few meaningful targets, you are compelled to focus. Robert Greene, in The 48 Laws of Power, called it “concentrating your forces.”

The first step of speed is subtraction.

The Friction Principle & Learning Rates

I once asked a Fortune 100 client how many new content pages they published per month.

“Per month?” they said. “We’re lucky if we get one live per quarter.”

Their process, if you could call it that, was an act of self-sabotage disguised as governance: ideation, review, brand, legal, localization, compliance, approvals, staging, QA, publish. Every step designed to reduce error and thus guaranteed to reduce progress.

What resulted most of the time was a beautiful slide deck filled with strategic ideas passed through the hands of dozens of stakeholders only to die quietly before it ever got to be implemented.

The irony is that friction often hides under the banner of quality. But friction doesn’t protect quality; it slowly erodes it by reducing the number of iterations that can happen in a given time frame.

To be clear, I’m a huge fan of process. I’ve often repeated the phrase spoken by my former boss, Peep Laja: “If you can’t describe what you’re doing as a process, you don’t know what you’re doing.”

But a process facilitates your desired outcomes, not the other way around.

Benyamin Elias wrote eloquently about our tendency to, over time, build cumbersome and burdensome processes that prevent, rather than facilitate, great work. Something to keep in mind.

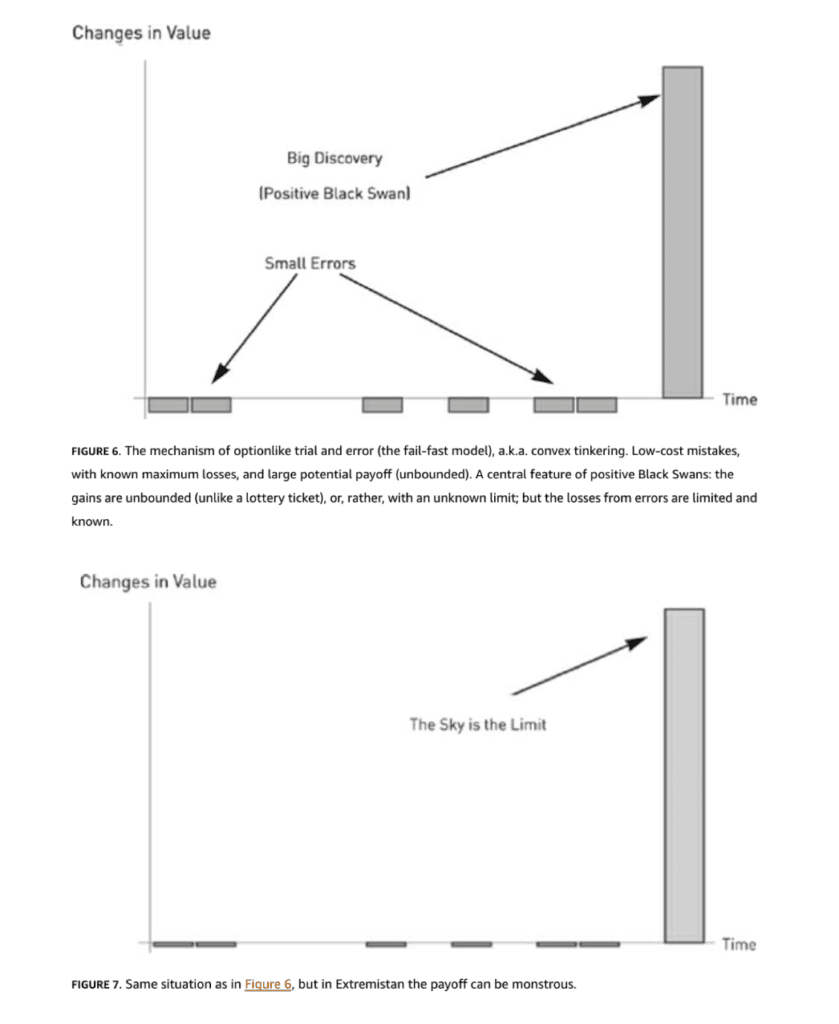

One thing that seems clear is that shipping a lot tends to result in more great work. I’ve seen this time and time again in my experimentation work. This is reflected broadly, as Ryan Lucht writes, riffing on Nassim Taleb’s idea of convex tinkering.

Geoffrey Miller, in his book The Mating Mind, once cited the research of Dean Simonton on creative output:

“Simonton’s data show that excellent composers do not produce a higher proportion of excellent music than good composers — they simply produce a higher total number of works. People who achieve extreme success in any creative field are almost always extremely prolific. Hans Eysenck became a famous psychologist not because all of his papers were excellent, but because he wrote over a hundred books and a thousand papers, and some of them happened to be excellent. Those who write only ten papers are much less likely to strike gold with any of them. Likewise with Picasso: if you paint 14,000 paintings in your lifetime, some of them are likely to be pretty good, even if most are mediocre.”

In the words of philosopher Macklemore, “The greats weren’t great because at birth they could paint. The greats were great because they paint a lot.”

So in a roundabout way, what I’m telling you is one of the first things I do, organizationally, is lower the cost or risk of an action, decision, or an experiment.

If you reduce the cost of an experiment, you increase its frequency. Increase frequency, and you increase the chance of discovery.

If an experiment costs $50,000, months of engineering and design time, and incurs a large risk…well, it better be a pretty damn excellent experiment to make it worth it.

If you can reduce the cost, you can increase throughput, and you can increase your feedback cycles and learning rate alpha.

Decentralization and the Cost of Permission

Speed is a structural property. You cannot will it into being through motivation alone, especially at a certain scale and employee count. It must be designed into the system.

Tony Hsieh of Zappos built one of the most elegant systems for speed by decentralizing decision-making.

In an interview with McKinsey, he said:

“Zappos strives to be like a city, where decentralized decision makers are united by common values.”

And in Delivering Happiness:

“We believe that in general, the best ideas and decisions are made from the bottom up, meaning by those on the front lines that are closest to the issues and/or the customers. The role of a manager is to remove obstacles and enable his/her direct reports to succeed.”

When decision rights are concentrated, every choice becomes expensive.

When autonomy is distributed, speed becomes ambient.

I’ve got a master principle in my own productivity as a manager and leader: don’t be the bottleneck. As I’ll cover in the next section, this often means responding quickly when something needs a review. More often than not, it means empowering someone to make a decision without my review.

This is often why startups, those chaotic little organisms, move faster: not because they are smarter, but because they are structurally allergic to permission seeking and overly rigid reviews.

Now, there’s nuance here. But it needn’t be burdensome. I remember, in my first job out of college, my CEO telling me, “If the decision costs less than $5,000, just make it.”

Your mileage may vary, and your number may be different; but if you trust your team, give them the power to make decisions in their domain.

Parallel Paths and Unblocking Bottlenecks

The simplest way to move faster is to stop waiting for everything to be done before anything begins.

Large companies love dependencies. Everything must flow through a sequence of handoffs, each waiting for the previous to complete. It’s serialized execution, but it’s also, colloquially, a whole lot of thumb twiddlin’.

Sometimes, you can just run things in parallel. You can publish while you plan. You can fix while you build.

When we design growth programs at Omniscient, we often fast track certain components before the entirety of the roadmap or the technical audit or whatever is complete. For example, if a core page is noindexed, we’ll fix it while we run the rest of the technical audit. We’ll fast track some obvious briefs before building out a topic and keyword TAM. We start with the obvious wins—update old content, fix broken pages, ship something useful—and build the system while moving.

Often, you can speed up outputs with zero reduction in quality simply by identifying and removing bottlenecks (especially if the bottleneck is YOU).

Mark Lindquist, my friend and a great marketing leader, once said:

“Since we have a pretty big team of contractors that I rely on, one of the biggest lessons I learned from Sujan was to never be the bottleneck holding up someone else.

If someone’s waiting for my approval on something and I put it off for no particular reason other than laziness, I’m losing days of work from them for something that will take me 5 minutes to keep moving.

That’s why I always prioritize feedback and keeping momentum on projects.”

I always try to keep things moving and try not to have people waiting too long on me.

Velocity as Culture

Speed is cultural as much as it is procedural.

If you’ve ever joined a company that truly moves fast, you know the feeling: meetings are efficient, feedback is instant and useful, and everyone defaults to action. The atmosphere hums with kinetic energy. Not stress, but aliveness.

In slow companies, every task feels like pushing a stone uphill. Slack messages linger unanswered. Decisions evaporate into the calendar void. People wait for permission not because they need it, but because that’s the default course.

Culture is the sum of tolerated behaviors. If you tolerate delay, you will get slowness. If you reward action, you will get speed.

Clean speed starts with leadership, but it is maintained by everyone.

Clean Speed

Speed, at its best, isn’t manic. It’s elegant.

The fastest teams I’ve worked with are calm. They don’t chase every idea; they don’t confuse busyness with urgency. Their speed comes from clarity and frictionless systems.

Clean speed is movement without noise.

It is what happens when clarity of purpose meets minimal drag. It’s the opposite of haste, and it’s far removed from chaos.

Jaleh Rezaei, CEO of Mutiny, articulated it perfectly in a First Round Review interview:

“A common misconception is that speed is associated with sloppiness, lack of thought and low quality. But speed is not the same thing as running around like a chicken with its head cut off. Real speed is moving fast towards impact and learning. It’s moving as fast as possible towards the most important thing, based on clear directives.”

Clean speed is what happens when every layer of the organization, from strategy to execution, aligns around learning faster.

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Field Notes