A few months ago, on a relatively unremarkable week, I wrote a listicle.

It was titled something like “Best Generative Engine Optimization (GEO) Agencies,” and at the top of that list I placed (surprise) my own agency, Omniscient Digital. To accompany it, we built a services page for GEO and linked the two.

That’s it. No digital PR push. No paid ads. No topic clusters. Not even Surround Sound SEO.

But the timing turned out to be everything.

A16Z dropped a piece titled “How Generative Engine Optimization (GEO) Rewrites the Rules of Search“. Alright, we’ve got a tailwind! Several clients forwarded me the article (and this stuff doesn’t usually rise to the attention of anyone but SEO nerds like me who spend free time on LinkedIn). The piece reframed an emerging conversation around SEO’s evolution into the generative era.

And suddenly, our two little pages—the listicle and the services page—were getting tons of traffic.

We started picking up links. Mentions. Inclusion in other lists we didn’t write, written by companies we do not know. All of this, due to LLMs summarizing and aggregating consensus recommendations across several sources, increased our already high visibility in LLMs. Which, if you follow my logic, should contribute to further mentions on new lists and pages (because people research using these tools), which increases visibility…ad infinitum (hopefully).

I’m not saying this visibility advantage will always stay, and it likely won’t (there are many, many factors that contribute to organic growth success, not to mention visibility in LLMs).

But it’s what got me thinking about the Matthew Effect and how it so often factors into organic success.

What Is the Matthew Effect?

The term originates from the Gospel of Matthew:

“For to every one who has will more be given, and he will have abundance; but from him who has not, even what he has will be taken away.” — Matthew 25:29

Merton borrowed this line to describe how, in academia, renowned scientists received disproportionate credit (and funding) compared to lesser-known but equally capable peers. Once you were visible, you attracted more citations, which led to more funding, which led to more visibility, and so on. A flywheel of prestige and progress.

It’s the compounding nature of advantage. Not merely “success begets success,” but systems that systematically reward early traction and visibility, making it harder for latecomers to catch up, regardless of merit.

And when you start to look closely, you see it everywhere in marketing.

The Double Jeopardy Law, Brand Affinity, and the Compounding Curse

In the 1960s, social scientist William McPhee observed the phenomenon that the less popular a TV show or radio program was, the less loyal its audience tended to be.

Shortly after, marketing scientist Andrew Ehrenberg described what he called the Double Jeopardy Law as applied to marketing and brand. He found that brands with higher market share didn’t just have more customers. They had more loyal customers. And smaller brands didn’t just have fewer buyers. They suffered from less loyalty among those buyers.

So the rich don’t just get richer, they defend their lead with a fortress of familiarity, brand salience, and consumer habit. The poor don’t just stay poor, they lose even their existing footholds as churn and drift sets in.

In digital marketing, we see this in organic search. A page that ranks #1 gets more traffic, more links, more dwell time and engagement signals. These user and linking signals reinforce its position, building some sense of an organic moat. The feedback loop strengthens. You can write a better page, but breaking in becomes expensive in competitive spaces.

And now we’re seeing it emerge again in generative search and GEO, though the dust hasn’t nearly settled on how these systems will function and change over time. Currently, however, brand mentions in relation to prompts have a strong correlation with brand visibility. And brand mentions beget citations. Citations beget visibility in AI-generated summaries. Visibility in AI begets more mentions as users copy, link, and expand on AI output.

Growth Loops, Flywheels, and Why Funnels Are Incomplete

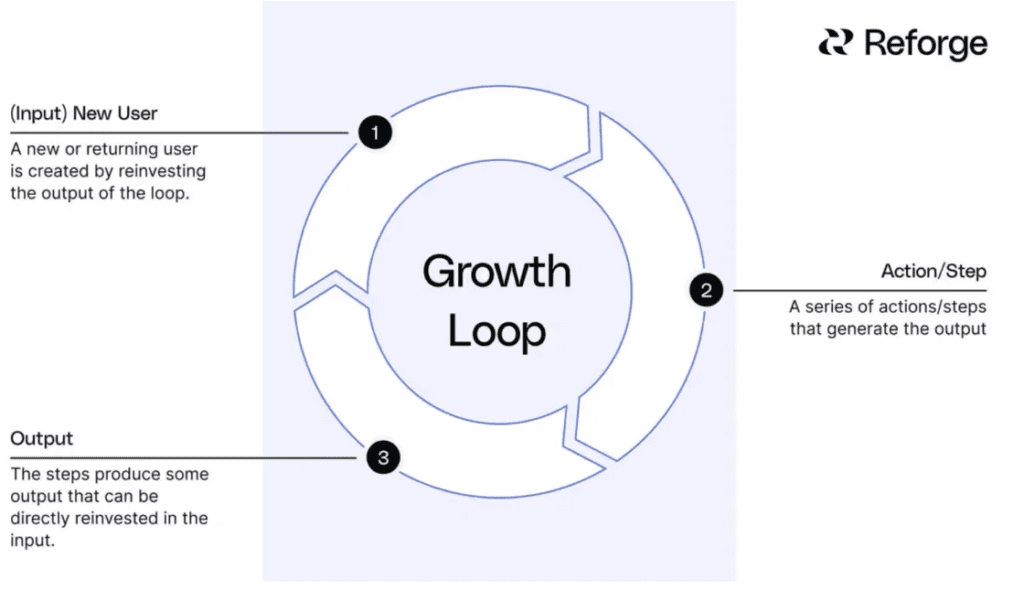

If the Matthew Effect describes a macro pattern, growth loops are the micro-level mechanics that power it.

A traditional funnel is a linear metaphor: attract, convert, close, delight. But loops are circular and self-reinforcing. As Brian Balfour at Reforge put it:

“Loops are closed systems where the inputs through some process generate more of an output that can be reinvested in the input.”

Let me riff on a few examples I could apply to my own business model (top of the dome here, I’m not saying these are actually explicitly planned growth loops we designed):

- Authority Flywheel: Win big client → do amazing work → publish case study → use as proof to pitch next tier → win even bigger client → repeat.

- Data/IP Flywheel: More clients → more benchmark data → better patternicity → higher quality consulting and work product gain → more case studies and referrals → more clients.

- Distribution Flywheel: Audience → algorithmic lift → more audience → cross-channel amplification → higher conversion and trust.

- Talent Flywheel: Great culture → top talent → elite client delivery → great case studies → better reputation → top applicants → loop continues.

Each flywheel is a manifestation of the Matthew Effect in a specific domain. And each requires intentional design, timing, and stewardship.

Virtuous vs. Vicious Cycles

Here’s the dark side.

Just as good work compounds into more good work, poor performance accelerates in the other direction.

A bad product experience leads to a bad review (or potentially even worse – an invisible but disappointed user who spreads negative feedback to their peers). That insidiously weakens lead generation and sales efforts. Which makes it harder to acquire new customers. Which makes it harder to generate revenue and profit. Which makes it harder to attract top talent. Which leads to product experiences. And so on.

Many marketing agencies (and startups) don’t die because of a single bad bet. They decay slowly into irrelevance by falling into a vicious cycle of reputational and experience decline.

So the question is not just: “Am I growing?” It’s: “Am I compounding in the right direction?”

This requires systems of telemetry and systems thinking. Early detection of slide. Rapid interventions. Feedback loops not just for acquisition, but for delivery, morale, and customer experience.

Strategic Implications for Marketers

If you’re in SEO, content, or brand, the Matthew Effect is a powerful mental model. It certainly focuses my attention on where I can build accumulative advantage, both for our own business and in building out organic growth programs for clients.

Design for compounding advantages as early as possible. That means:

- Get early mentions in places LLMs are trained on (Reddit, Wikipedia, G2, podcasts, blogs), particularly within nascent lanes and highly specific topics mapping to your differentiated value proposition.

- Build hard-to-fake signals: original data, expert-centric assets, opinionated content.

- Develop systems to detect slide and intervene early (e.g., NPS drops, declining backlink velocity, movements in leading indicators).

- Don’t think merely in terms of linear funnels, but in terms of compounding loops.

- Invest in the nodes that feed long-term growth: brand salience, distribution, proprietary IP.

Quick hack: use o3 and upload as much business context as you’re comfortable with. Ask o3 how you could apply the concept of the Matthew Effect to your own business. It will give you many ideas worth considering.

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Field Notes